Investigating the dynamic Peruvian polity (1)

Issues on descentralized budget governance

The Peruvian constitution of 1993, while stating a clear cut difference between the three powers, concede the Parliament a preponderance of its power over the Executive. Peruvian institutions have been facing social unrest periods in the last thirty years. The response of politicians and institutions has focused on employing legal tools enacted by the same Constitution. In the case of the policy of decentralized governance, the implementation has seen the national scale administrative competencies and budgets to be transferred to the regional and local levels. The new atomized but legal prerogatives of local authorities, are mainly regarding to infrastructure projects. The transfered handling of these local-focused projects compensate the maintained control on the budget of bigger projects at national scale. IN these cases only, the national authorities cannot afford to control but to coordinate only its delivery at lower levels of government.

The scandalous management of accounts in the public offices at national, regional and local levels, is a neverending struggle. In this regard, one shall mention widespread public disaproval and promp reaction of Judicial power and control institutions in the prosecution of corruption cases accross all ranks of elected and non-elected public officials. Despite these practical contermeasures it is also remarkable the maintenance of patronage exerted by autonomous political leaders, at regional and local levels mainly. This is causing the increase of the employment of the means of corruption at their dispossal, in the context of increasing local budgets.

The effects of the above mentioned changes and vices of public administration, on the availability of public services, is giving left-leaned groups and protesters arguments to denounce current constitution as oppresive and reactionary. Thus, this reading of the emerging conflicts between organized citizens and the State, focus on institutional arrangement, geographical scales and public officials behavior. Problems and oportunities arise during the frentic confrontation periods at every territorial scale. The context of the evolution of Peruvian public institutions occurs in a free market operation.

Geographic and political determinants

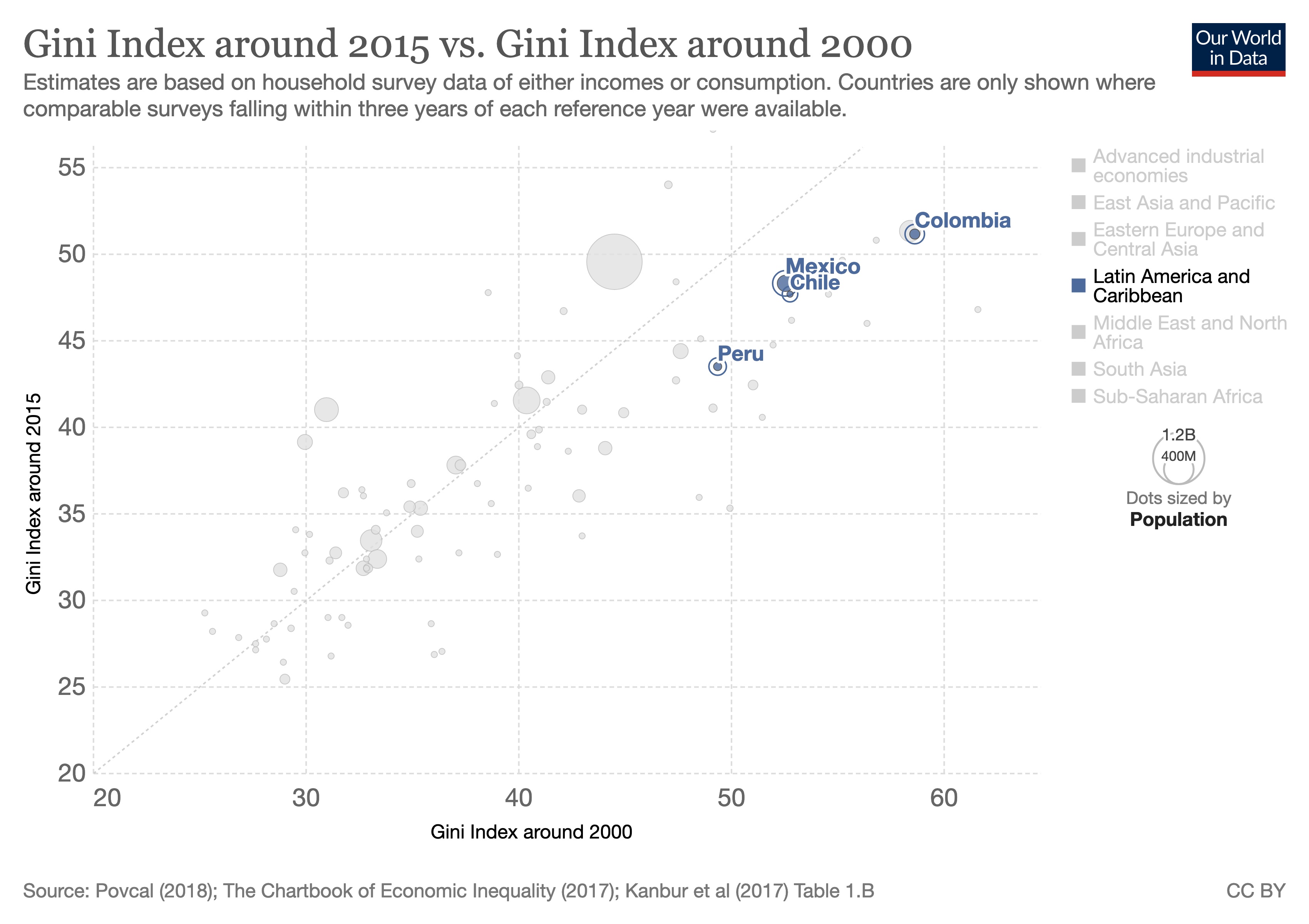

The 1993 Constitution also enacted the establishment of a common free-market and deregulated economy across the geographical scales. This neo-liberal policy has resulted in a increase of wealth across the country, including better of health conditions and inequality reduction. Comparing current socio-economic conditions with those in the early nineties, wellbeing among Peruvians has been progressing despite conflicts and government mismanagement. To better comprehend the relationship and operation of state levels and economic powers acting within the range of the Constitution, it is necesarily to add the spatial environment where these struggles occur.

Marx and Engels “often saw political action as irrelevant to economic development” (Marx and Engels cited by Sciabarra 1995)1. Perhaps, this affirmation can be empirically validated by looking the performance of the Peruvian economy during the last thirty years. Moreover, Marxian theory of the business cycle also “emphasizes the economic or material base of political structures and processes”1. In this regard, informal labor is materializing in wellbeing. Informality is a mechanism employed by a vast majority of workers to endure difficult conditions and create wealth even during turbulent politic moments that are being naturalized as part of the whole trajectory of society evolution. This survival estrategy, has allowed the state economic policies to follow healthy trajectories being flexible, effective and responsive after major shocks from Lehman crisis to Covid pandemics.

Autonomous operation and spontaneous order

Institutional learning, within the framework of the Constitution, during this period, is giving results as far as some economic institutions gain respect and strenght. This is the case of the macro-economic policy custodiated by the Parliament, the Ministry of Finance and the autonomous Central Bank. Meanwhile, this achieved and unstable state of affairs provides ground to further advance in the evolution of a popular capitalism. In this regard, Marx “suggest in several occasions that a fully free and mobile market with ‘complete freedom of trade’ offers the masses the best possibility for revolutionary transformation in the production process” 1

Thus, this brief account of the latest Peruvian polity struggle and its material realization is providing the empirical substrate to identify and describe, the socio-spatial conditions where its historical evolution occurs and further explore the ways to interpret and influence it accordingly, away from rational planning practices, while embracing the turbulence and the order it generates that is due to its particular geographical and antrophological nature.